Recent flooding at the former confluence of Effra tributaries in Herne Hill: anti-flooding measures have been undertaken in Dulwich to alleviate the effects of events such as these downstream: cf photo 8.

Although

the former course of this small southern tributary of the Thames is

quite well documented from its main sources in Upper Norwood, via

Brixton, to its current outfall near Vauxhall, it is sometimes referred

to as 'Lambeth's lost river' since it has been culverted under the

streets of London for over 150 years. There is still some controversy

over its precise drainage pattern, and also over the location of its

confluence with the Thames at different times. Its outlet was, in common with many other tributaries of the Thames, used as a small haven and commercial quay for riverside industries, but, contrary to local folklore, it was too small and shallow to be navigable. Queen Elizabeth may have used the roads along the Effra valley to visit Sir Walter Raleigh (who occasionally used a house he owned in Brixton) and others of her court favourites south of the Thames (as she

once picknicked under the tree that gave its name to Honor Oak), but,

alas, even that is speculation. The main contribution of the River Effra to the develop- ment of Lambeth was as a means of disposal of its effluent, as Jon Newman makes clear in his excellent book: 'River Effra: South London's Secret spine'. Recently the Mayor of London announced that stretches of the Effra,

along with other hidden London rivers, are to see the light of day once

again. However, as we shall see, some parts of the Effra's upper

reaches at least can already be seen above ground in that part of its

basin that focuses on Dulwich, and some of its original sources were not

in Lambeth at all, but in the neighbouring Boroughs of Croydon and

Southwark, and even in more distant Lewisham. As we have already seen, there

has been some controversy over the full extent of the Effra's drainage

basin, the main course of the river and its tributaries, and its

significance to South London's development, all of which I shall examine

here. As a geogapher I

hope to illustrate ways in which the River Effra helped to shape the

local patterns of land use, transport and settlement, and to give

Dulwich in particular its distinctive character.

a) Location and outline of the Effra Basin:

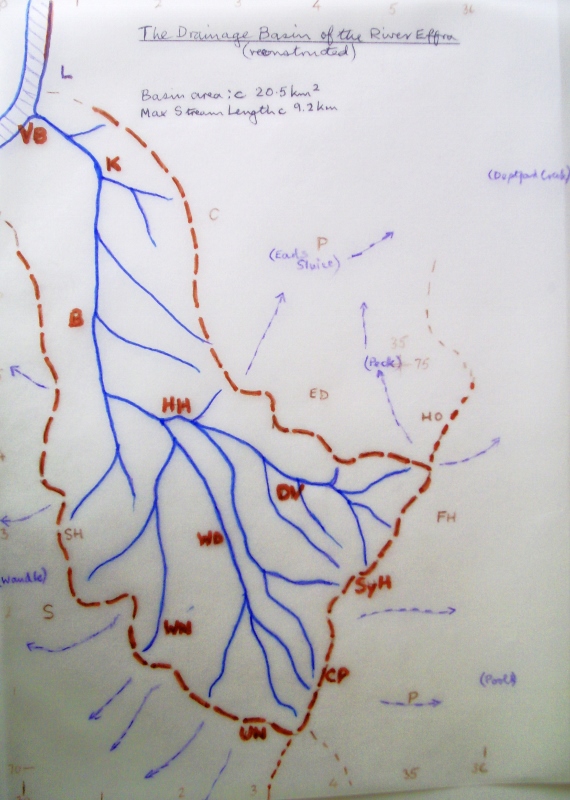

Map 1 : Reconstruction of the former drainage basin of the River Effra.

The Effra drainage basin is located in the central area of inner south London, focusing on the River Thames at Vauxhall. It is roughly trapezoid in shape, its long axis aligned from SSE to NNW, narrowing slightly in that direction. Its southern and south-eastern watershed (marked in brown above) is the 100m high, steep, narrow ridge that extends from Upper Norwood (near the borders of Lambeth and Croydon), along Sydenham Hill (in Southwark) to Westwood Park (just in Lewisham). There is just one col cutting across the ridge - carrying the South Circular Road at Horniman's, Forest Hill (picture 1). Few other roads cross the ridge directly, and railways skirt round it or tunnel through. Drainage south and east of this prominent watershed is to the Pool River, which joins the Ravensbourne in Catford, and reaches the Thames via Deptford Creek. Drainage to north and north-east is via the Peck, Earl's Sluice and Neckinger towards Surrey Docks.

1. The Sydenham Hill watershed (Horniman's is off left); 2. The easternmost source of the Effra, along rain

falling here drains to the Effra via Dulwich (off right). Hornimans' Railway

Nature Trail. )

The western watershed is a northward-projecting spur from the Norwood Ridge that separates the Effra from its much larger neighbour, the Wandle; the latter reaches the Thames at Wandsworth. The north-eastern watershed consists of lower and less regular slopes that separate the Effra from the former Rivers Peck and Neckinger, and the Earl's Sluice that fed Surrey Docks and the Surrey Canal. There is a lower, secondary interfluve running from Crystal Palace to Knights Hill and Herne Hill that separates the Sydenham Hill and Dulwich part of the Effra basin from that of Norwood and Brixton. The Effra is a small basin - only about 20 sq km. The maximum stream length (between Westwood Park and Vauxhall) is just over 9 km (or 10km if the possible former extension to Bermondsey is included, see below); the altitude range within the basin is quite high - about 111 metres or 360 feet. The highest point (at Upper Norwood) is also the southernmost, but there was a continuous line of springs at between 80 and 100 m OD along the imposing 5 km ridge that was Surrey's 'Great North Wood'. The Effra headwaters they fed followed different paths to join up at Brixton, viz: (i) from Upper Norwood and Norwood Park direct via West Norwood, (ii) from Crystal Palace and Gipsy Hill via West Dulwich and Herne Hill, (iii) from Sydenham Hill and Dulwich Woods via Belair Park and Herne Hill, (iv) from Peckarmans Wood and Sydenham Hill via Dulwich Park and Herne Hill, (v) from Eliot Bank, Hornimans Park, and Westwood Park via Dulwich and Herne Hill. There were also springs at lower altitude in East Dulwich (eg Dawson's Hill), North Dulwich (eg Sunray Gardens), and Tulse Hill, and at the base of the Thames river terraces further downstream (eg Stockwell and Kennington). There was indeterminate drainage in the marshy floodplain around Vauxhall and Kennington, and some evidence to suggest the Effra may also have extended originally in the direction of Bermondsey and the Neckinger basin. b) Rocks, Soils and Land Use:

Geological Background: Most of our area is underlain by young sedimentary rocks, deposited about 8 million years ago in an ancient sea that invaded a deepening down-fold of the Chalk rocks occupying most of what is now southern Britain and Northern France. The sediments were initially coastal sands and gravels, but as the sea deepened, great thicknesses of offshore mud were laid down to become the London Clay. Further short marine transgressions deposited thin layers of younger, less consol- dated sands and gravels on top, before the whole assemblage was uplifted, tilted, exposed to the elements, and weathered. This produced the funnel-shaped London Basin we see today: with Chalk at the base (exposed at Greenwich, and south of our area in the North Downs), then Bagshot Sands (found mainly as sandy heathland south and west of London), next the London Clay which dominates most of the region, and finally the Woolwich and Reading Beds which locally provided a protective sandy and pebbly cap on top. The fore-runner of the modern Thames initially drained this basin east-north-east across plains that are now occupied by the North Sea, but the development of the drainage pattern was interrupted in a big way by the Pleistocene Ice Age(s) from about 2 million years ago. Ice sheets spread into the northern part of the region and diverted the proto-Thames trunk stream southwards to approximately its present west-east line. Powerful meltwater streams enlarged the existing main and tributary valleys and spread material from the ice (drift) over tundra-like frozen ground, well beyond the ice front. When the ice finally retreated 10000 years ago the topography, soil, drainage pattern, and even the climate, were very different from that either before or since. This was a new landscape and environment to which the newly forming Effra and its neighbours had to adapt - a process that may still not be complete.

Soils, slopes and landforms: London Clay is the bedrock underlying nearly all of our basin. It is a stiff bluish-grey clay when undisturbed underground, but it weathers very quickly upon exposure to a pale yellowish brown colour, which becomes dark brown where soils have formed on it. It is composed of very fine-grained clay particles with the tiniest pore spaces in between. These quickly become filled with rain water, which can only permeate and move through the soil very slowly by capillary action, and therefore the soil is normally heavy and cloying because of its high water content (as local gardeners will testify), and highly impermeable. It will expand readily and heave upward if the interstitial water freezes. However, when it dries out in summer it shrinks, cracks open up at the surface, and the soil particles lose their physical and chemical bonds: the soil can then become very friable and susceptible to erosion by running water. In hollows and at the foot of slopes water collects quickly, can't drain away, the ground becomes waterlogged and puddles form, as happens frequently below Dulwich and Sydenham Woods, acting like a giant sponge (picture 4). Regular cycles of wetting and drying, freezing and thawing, expansion and contraction, have the effect of causing the soil to creep steadily downhill. In extreme circumstances a whole soil mass will slump or slip, producing irregular and unstable slope profiles and potential engineering and structural problems, as the early railway builders and many local residents (including St Stephen's Church, South Dulwich), have discovered to their cost.

Because it is soft, and weathers and erodes easily, London Clay generally forms areas of low relief, but the southern rim of our basin rises to over a hundred metres (330ft) above sea level in less than 10 kms, with locally very steep gradients. This is partly because of the 1 to 3 metre gravel capping that covers and protects the clay here, particularly at Crystal Palace and Upper Norwood. The sand and gravels, though only partially consolidated, were permeable and more resistant to physical and chemical weathering than the clay beneath them, and they readily absorbed rainwater, rather than shedding it as runoff and initiating erosion. However, when the rainwater percolating through the gravel reached the impermeable clay beneath it ran along the junction until it reached the ground surface below the summit ridge to form the line of Effra springs. The level in the rocks below which they are saturated with percolating water is called the water table, and its depth below ground level tends to fluctuate according to how much rain there has been. The water table here, as in most of England, has lowered considerably in recent years, so the former springs are now dry. However, water still collects at the surface after rain, and there are semi-permanent springs lower down. It is likely this lowering of the water table will continue in the future under the influence of global warming (for more information see Appendix 1 below). Water issuing from springs tends to sap or undercut the slope above, causing it to steepen and slowly retreat, evidence for which can clearly be seen in Dulwich Woods (picture 5a). Furthermore, these slopes face north and receive little sun, particularly in winter, and therefore they are also very susceptible to the freeze-thaw action described above; this reinforces and accelerates the steepening effect. In the lower reaches of the Effra basin the London Clay is locally covered by a veneer of silt sand and gravels deposited in the valleys by the proto-Thames and its tributaries at the end of the Ice Age. These deposits were then eroded and cut back to form river terraces raised slightly above the floodplain, some of which make up the lower interfluves of Lambeth and Southwark. These also fed springs, formed islands in the marshes, and provided firm dry sites for building houses, roads, and railways, hence facilitating the explosive growth of South London in the 18th and 19th centuries.

3

The dry Ambrook valley on Dulwich and Sydenham Hill Golf Course. 4 Runoff on Dulwich Common (from Sydenham

Hill beyond)

Note the foreground terrace, and the steepening

towards Dulwich Common.

Land use, environment and settlement: There are significant contrasts between the Dulwich and Lambeth parts of the Effra Basin in the way the land is used, most notably in the ratio of built up area to open land. In the basin as a whole, approximately three-quarters of the land is classed as built-up (consisting of residential, industrial, commercial and public buildings with their curtelage, and the transport infrastructure that serves them), whilst the remaining quarter is classed as open land (which here is mainly parks, playing fields, and cemeteries). This built up/open land ratio is not as high as might be expected in the Inner South London Boroughs of Lambeth and Southwark (which are generally perceived as being particularly overcrowded), but the ratio does increase substantially from south to north (ie from Norwood to Kennington and Central London), which is what one would expect. What is surprising, though, is that this built up/open land ratio suddenly decreases very sharply (to less than parity) in Dulwich. There can be few residential areas of comparable size within four miles of the centre of any world metropolis that can claim to have less than half of their land built over, as Dulwich can. Moreover, this inner city area includes a significant swathe of natural woodland, three Local Nature Reserves, and an 18-hole Golf Course, in addition to parks, allotments and sports grounds (pictures 3&4 ). It is not that the land is difficult to build on, or that it is not in demand - far from it: Dulwich is one of the most sought after residential addresses outside London's West End. So how has this anomalous situation come about, and what is its significance?

The woodland is the surviving part of the Great North Wood of Surrey (to distinguish it from the Forest of the Weald further south). It has been considerably modified over many centuries by human activity. Clothing the steep-sided Norwood and Sydenham Heights, it was a natural boundary between the growing London metropolis and its rural hinterland, as well as an important resource. The steep slopes, wet soils, and dense vegetation made it a place of refuge rather than permanent settlement until recently, but it has been coppiced since medieval times, for building, firewood, and charcoal burning. Only in the 19th century, as transport improved and London's environment deteriorated, did wealthier citizens move to the higher parts of Norwood, Sydenham, and Forest Hill to take advantage of the fresh hill air, clean spring water, and sweeping vistas of the Effra watershed. Their large houses and gardens were inevitably expensive to maintain, and most have now either been converted into flats and nursing homes, or replaced by smaller, higher density properties. While the original forest was dominated by native oak and hornbeam, the woodland we see now has a much greater variety that includes introduced species like sycamore and horse chestnut, colonisers such as holly and birch, and escaped garden shrubs and trees. In response to public pressure, much of the remaining woodland is now protected and managed by ecological groups, local authorities, and private landowners (such as Dulwich Estates). For more detailed information on the ecology of the woodland see the 'Real Forest Hill?' page of this website. On the lower slopes of the ridge, Dulwich and Sydenham Woods give way to allotments, the Golf Course, and playing fields. This was the original Dulwich Common - largely unimproved grassland used for grazing of livestock, since the land was wet and subject to downslope drainage of cold air in winter. It was also relatively inaccessible because it was marginal to the ancient monastic and manorial landowners of Kent and Surrey, and the Parish Vestries which took over their social and administrative functions. Further north still, around Dulwich Village, the confluence of the growing Effra headwaters produced the lush water meadows used mainly for dairying and livestock fattening as London's demand for food grew. Accessibility was better here, but unlike neighbouring Camberwell and Peckham (which had a veneer of more sandy soils on top of the London Clay) the wetter clays of Dulwich were less suitable for crop growing or market gardening. This land was the main part of the Manor of Dulwich that Edward Alleyn acquired, and where he built his College of God's Gift. As a result of careful management and deliberate policy it is still occupied mainly by the Old College, its modern successor (later rebuilt on Dulwich Common), Belair Park, and Dulwich Park (where Dulwich Court Farm used to be), and more recently by several sports' clubs. Residential development has been confined almost entirely to the margins of the Dulwich basin where are located still the only through roads and railways - along Lordship Lane in the east, Upper Sydenham and Crystal Palace in the south, Herne Hill and Denmark Hill in the north, and West Dulwich and 'the Norwoods' on the west. This house-building began in the 18th century as upper middle class ribbon development along coaching routes such as the Brighton and Portsmouth roads, then from the mid-19th century as nodes around railway stations like Herne Hill and West Norwood, before spreading out and joining up in the later 19th and 20th centuries as omnibuses, trams, bicycles and motor cars became increasingly widespread. Working class housing was packed into less salubrious plots within walking distance of factories and other places of low-paid employment, eg backing onto railway lines (such as those at Loughborough Junction), or near gas works and other public utilities, as at Nine Elms (Vauxhall). Commerce and public services such as shops, schools, churches etc broadly followed the residential development, but it is notable that there were no old-established markets in south Lambeth or Dulwich, although Goose Green in East Dulwich had a notorious Fair. Manufacturing has always been constrained by the need for access to cheap land, labour and materials - initially via navigable water, then railways, and more recently trunk roads. These were only found in the Thames-side district from Waterloo to Nine Elms. Whilst Norwood and Brixton may have their share of shops and public services, and even some offices and light industry, it is notable that Dulwich is characterised (some would say dominated!) by no less than six large schools (four of them well-known independent schools), whilst commerce and industry are almost completely absent. Apart from schools, whose facilities are widely popular in the community, it is well-known for its sports clubs, its Picture Gallery, and its cultural and amenity groups, and literally on its borders are Horniman's Museum and the site of the Crystal Palace Great Exhibition Centre - a stimulating cultural and social environment indeed. While it would seem that these defining characteristics of Dulwich can ultimately be traced back to the vision of Edward Alleyn and to his successors, as well as to a number of influential landowners and residents, it is also evident that the environment and physical features of the Effra Basin played a major part.

c) Following the Effra downstream:

(Diagram 1: Reconstructed Valley Profile from Sydenham Hill to Vauxhall, via Dulwich and Brixton:)

The profile above has been reconstructed with the aid

of Ordnance Survey map data, supplemented and verified by study of the

slopes on the ground. It broadly shows the typical concave-upward long

profile of most rivers in temperate latitudes, but it is not completely

smooth: there is local steepening on the Golf Course, in Dulwich Park, and beyond Herne Hill, with flatter profiles on Dulwich Common and approaching Herne Hill.

The steeper gradients occur where tributaries join, increasing the

stream's erosive action; the flatter sections are surviving fragments of

earlier flood plain where deposition took place. The long profile

is steeper than would be expected in a short, lowland stream in Britain,

particularly so in its source region, and it has a very short flat

flood plain section close to its present-day outfall relative to its

overall length. Nor is the drainage basin symmetrical in shape (the

longer tributaries are from the east, not the south or west), and

the inferred stream pattern is of high density, especially in its upper

and middle reaches.

All

this suggests a relatively young stream that has not had time to adjust

fully to present day topographic and climatic conditions, and one where

significant changes in its environment and discharge have occurred over

the years. Such youthful or disrupted rivers are more volatile in

behaviour, and flood more readily than their fully graded

counterparts, one of the reasons the Effra was culverted downstream.

These characteristics can be explained by the underlying geology (mainly

London Clay), by its climatic and morphological history (initiated at

the end of the Ice Age and subject to fluctuating discharge and a high

water table ever since), by its location near the mouth of the River

Thames (which is sinking, is tidal, and used to be subject to flooding

and changes of course), and the growth of London (which constrained then

culverted the channel, and caused increased runoff).

5a The artificial leat collects spring runoff from the steep 5b Source of the Ambrook River (Effra headwater). slope below Sydenham Hill, to reduce path erosion. Note the compacted clay soil, and steep, rounded slopes.

6 The view from Dulwich & Sydenham Hill Golf Club, across the Dulwich basin to the W Norwood (Knights Hill) interfluve on the skyline. Dulwich College is in the middle ground. The Herne Hill gap is the lower ground behind and to the right, with West London visible through it.)

The stream course we shall concentrate on is neither the main Norwood stream nor the longest Forest Hill branch, but an intermediate one that is more typical of the whole, and easier to identify and follow. It begins at former springs below Peckarmans Wood which can be accessed from a gate near the junction of Crescent Wood Road and Sydenham Hill, SE26. They are in the central and highest part of the spring line that extended in an arc for about 8 kms along the ridge of hills between Streatham Common and Nunhead. Rising at about 105 metres OD, rills and gulleys drain steeply down in a north-easterly directionas as the Ambrook river, through small ponds in Sydenham Woods to the edge of the Dulwich and Sydenham Hill Golf Course at about 60 m OD. Here there is a near level terrace on which the allotments, Clubhouse and South London Scout Centre are located. The stream then follows an obvious valley (now dry - picture 3) which turns north towards The Grove Tavern on Dulwich Common (the site of Dulwich Wells, which for a short time late in the 18th century rivalled the better known Sydenham Wells and Beulah Spa). Our stream was then joined by other headwaters flowing from East Dulwich and Forest Hill, and flowed north-west across what were once the water meadows of Dulwich Court Farm, now Dulwich Park. There is no channel to follow here, only an irregular line of oak trees winding towards the Park Lake. The river drains the lake over a metre high weir and turns north-west towards Old Dulwich College in a prominent 2 metre wide channel. By the Old College Gate it used to be joined by a ditch that brought more tributaries from Sydenham Hill via Dulwich Mill Pond (this was later covered over to produce College Road's wide grass verge). A short stretch outside Bell House still carries occasional storm water, and there is a tall iron 'stench pipe' marking the line of the Victorian drainage/sewer pipe beneath.

7a. The

Dulwich & Sydenham Hill branch of the Effra draining Dulwich Park Lake.

From

the Old College downstream the river flows entirely underground,

although it is still possible to trace its route by following surface

contours and the lie of the land. It

continued across former marshy meadows (now playing fields) in West

Dulwich to be joined by more Effra headwaters from Crystal Palace (some

of that water is still visible just to the south in Belair Park).

The water meadows around Dulwich Village were the eponymous "Dilwyhs"

(fields where the dill flower grew). They sit in the bottom of a

north-tilted saucer whose rim is the watershed of the Dulwich part of

the Effra drainage basin.

The only way for the water to exit the Dulwich basin was via a narrow

gap in the rim at Herne Hill associated with a deep-seated fault in the

rocks. These combined Effra headwaters approached Herne

Hill via present-day Winterbrook Road, turned west along Half Moon Lane through the gap to Brockwell Park, to be joined by further tributaries from West Norwood.

It in turn joined the main Effra River flowing from Upper Norwood and

Streatham Hill via Brixton Water Lane (sic) and Effra Road, continuing

north to Kennington, where it turns abruptly west to Vauxhall. The last section of

the river is shown on my profile as a dotted line because the position

of its confluence with the Thames was variable until it was finally

stabilised by Joseph Bazalgette and the Metropolitan Board of Works in

the 19th century. There is growing support for the view that before the 13th Century the river

may have continued further north through Southwark to

link with the Neckinger in Bermondsey.

8.

The Herne Hill gap from Brockwell Park. The Dulwich branch of the Effra

came in from the right (approximately at the railway bridge), was

joined by tributaries from West Dulwich and Norwood, then continued left

along the line of Dulwich Road to Brixton (picture 9). Note the railway was

built up on embankments across the low-lying marshy ground through

Dulwich.

(9. Looking WNW along Dulwich Road from Herne Hill. The Effra roughly followed this line towards the main Effra confluence in Brixton (half a mile away). The slopes of Brockwell Park are on the left, and those of Herne Hill behind the buildings on the right.

d) Summary: Ten ways the Effra has influenced Dulwich: (1) In its upper reaches springs

steepened the slopes, made the clay soils waterlogged and unstable,

encouraged woodland rather than occupation, and made access difficult

- hence it wasa barrier to movement.

(2) Roads heading south

out of London found it easier to skirt the steeper slopes of the rim of

the Effra Basin, following the Thames terraces where possible, and

therefore by-passing Dulwich. Because there were few people and

therefore little need for access south of Dulwich (at least until the

Crystal Palace was built), College Road was never publicly maintained:

it was improved by an early 19th century Penge grazier to give

him access to land leased from the College - hence London's only

surviving Toll Gate. (3) East-west road connections in

Dulwich were limited until quite recently to Court Lane (from the

Lordship Lane turnpike), and Burbage Road and Half Moon Lane to Herne

Hill - significantly following the general slope of the Effra basin.

Dulwich Common was effectively just a local lane until the new Dulwich

College was built in the 1870s, carrying very little traffic. The

present South Circular Road was an ill-considered product of 1940s

planning policies, whose principal modern legacy is a perpetual stream

of through traffic which effectively cuts Dulwich in two. (NB: There was

no bus route through the Village or along the Common until the

1960s.) (4) The railways had

to be raised above the Thames and Effra floodplains on viaducts (whose

arches provided workshops and cheap dwellings for the working classes).

They then skirted the Dulwich meadows on embankments, and cut through

the steepest slopes by means of expensive cuttings and tunnels, as at

Crystal Palace and Tulse Hill. A particularly interesting case was the

'High Level' Railway that followed the rising Effra watershed for just

three miles from Nunhead to Paxton's 'Crystal Palace': it had to tunnel

twice through the winding ridge at Sydenham Hill to reach its elaborate and ornate terminus. With few residents or businesses along it, it

could hardly have been viable even in the Palace's Victorian heyday. (5) Although close to Central London, the air

in Dulwich was relatively clean and unpolluted. This was because

Dulwich was upwind (west and south-west) of the heavily polluted

industrial areas of Thames-side and the East End. It was therefore

recognised early on as a valuable 'green lung' for London: Dulwich

Park was a direct outcome, and it is still enshrined in Southwark's

planning policy.

(6) The steep north-facing slopes to the south encouraged rapid water movement and cold air drainage

into the Dulwich basin, increasing the incidence of fog, frost and

dew, particularly on grassy areas such as Dulwich Common. Dulwich is, on average, a degree or two cooler than the mean temperature of London's 'Metropolitan Heat Island'. (7) The combination of decreasing slopes, clay soils, high water table, and

cool damp climate encouraged the water meadows which originally gave

Dulwich its name, as well as its prevailing green appearance and leafy environment. These

conditions encouraged grazing rather than crop-growing, but, once

drained, the clay soils and gentle slopes were ideal for allotments,

parks, gardens, and playing

fields. (8) The environment also later encouraged the successful planting of a wide variety of imported trees

and shrubs, providing another of Dulwich's defining characteristics -

especially its oaks, horse chestnuts, cedars, maples and plane trees. As a

result of the high water table, Dulwich has one of the highest densities

of ponds and water features

in London, which provide distinctive habitats for wildlife and

additional attractions to both residents and visitors.

(9) The site, form and fabric

of Dulwich Village itself also owes much to the river: the original hamlet was on the low terrace just to the east of the Effra flood

plain, the wealthier houses and the Old College were built overlooking

the river, and storm

ditches alongside College Road became today's wide grass verges. Croxted Road (the 'crooked street') followed the winding course of the West Dulwich branch of the river.

(10) Some of the older buildings still show evidence of the use of local materials,

eg timber products from the Great North Wood and iron forged with the aid of its charcoal, as well as reeds, withies and clay

tiles from Dulwich Common, and the distinctive yellow and grey London Clay

bricks from Sydenham Hill and Upper Norwood, and from Dawson's Hill in

East Dulwich.

In summary, it can be seen that the Effra Basin's location and natural

environment have combined with historical precedent, planning and

management policies, and market forces to make Dulwich a particularly

desirable place to live, for those willing and able to pay for the privilege, all of which is reflected in its current economic and social geography.

e) The Effra and Dulwich: past, present and future:

In ancient times the low terraces of the Effra flood plain led Stane Street (the Roman Road from the Channel coast) towards the first Thames crossing at Thorney Island (now Westminster). In Tudor and Stuart times the valley gave access to fresh air, forest resources and foodstuffs for the English Court at Westminster, for the City of London's wealthy merchants, and the growing population that serviced them. In the 18th and 19th centuries the basin supplied much of the water that allowed Lambeth and Southwark to become important dormitories for London (and a ready means of disposing of their effluent!), while in recent times the area has increasingly nurtured educational, cultural and leisure opportunities for a wider community. Dulwich is now known and appreciated for the distinctive quality of its suburban environment, all of which owes much to its earlier Effra connections. But what of the future?

The recent announcement that 'Lambeth's lost river' is to be uncovered again for environmental reasons is certainly ironic, since it was sent underground in the first place largely because of its contribution to South London's chronic flooding and water-borne disease problems! The Effra is too small ever to become commercially important of course, but experience from the successful reclamation of former polluted water areas in the Lea Valley, Docklands and elsewhere offers hope that the environmental benefits may lead to some improvements in residential status and desirability in presently disadvantaged parts of Lambeth.

Will climate

change resulting from global warming alter Dulwich's character?

Will Brixton become the new

Dulwich?

Comments and enquiries by email to martindknight@gmail.com please.

Appendix 1: Wells, springs and the movement of water within the Effra basin: see the next page of this website (this Appendix has been inserted in response to specific enquiries I have

received relating to the depth and properties of wells and springs in and around Dulwich).

Picture 10: Spring water (flowing to the right) initiating a small runnel in the heart of the Dawsons Heights Estate in East Dulwich, before turning west through the site of former brick and tile works to the Dulwich Basin.*

* Footnote: There were traces of ancient banks and ditches atop Dawsons Hill, which commanded fine views over much of south and central London. A local tradition (unverified) has associated it with the gathering of the Roman cohorts that swooped on Boudicca and her troops when they sacked the City in 69 AD. There was therefore considerable controversy when the estate development was proposed by Camberwell Borough Council in the 1950s, on historical, hydrological, architectural and aesthetic grounds. The eventual development, based on plans submitted by a newly qualified female architect from Edinburgh, has received favourable comment in architectural circles over the years, but (as is so often the case) a mixed reception from residents, neighbours and those who value uninterrupted views (see for example the view from Westwood Hill in the 'Real Forest Hill?' page of this Website). It has been likened, rather unkindly, to a giant cruise liner, or an Assyrian ziggurat!

Picture 11: The Dulwich Park Flood Alleviation Scheme

Appendix 2: Effra images relating to Lambeth, but referred to in the main text above:

12: An Effra spring in Westow Park; 13: Effra channel in Brockwell Park; 14: View over the Effra valley from Norwood Park to Knights Hill.

15: Brixton Rd: the 'Washlands' verge once accommodated the Effra 16: Kennington Park, where the Effra turns west towards Vauxhall 17: Outfall: Effra sluice at Vauxhall Bridge (low tide)